(Leiden) In a Dutch museum, sounds of hip-hop music echo alongside sarcophagi and statues, in what exhibition curators say is an attempt to show the influence of ancient Egypt on artists with African roots.

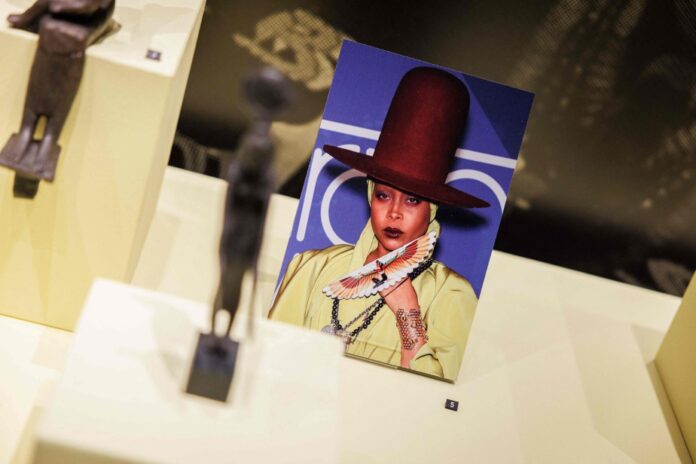

A photo of Beyoncé as Queen Nefertiti and a video of Rihanna dancing in front of pyramids are displayed near ancient busts. In the middle of a room sits a golden mask that seems to belong to a pharaoh, then turns out to be a modern sculpture reproducing the cover of an album by rapper Nas.

These pieces featured in the Kemet – meaning “black earth” – exhibition at the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden (National Museum of Antiquities) in Leiden have drawn the ire of Egypt, which reportedly banned archaeologists at the Dutch museum from excavating a key site.

The Egyptian Antiquities Service said the museum was “falsifying history” with its “Afro-centric” approach and denounced the appropriation of Egyptian culture, according to Dutch media.

Some comments on social media were “racist or offensive in nature” after the controversy erupted, even the Leiden Museum lamented.

So what was meant to be an uplifting celebration of “Egypt in hip-hop, jazz, soul and funk” became the focus of a cultural battle.

The canal-side museum in the picturesque university town is far from resembling an arena, though, as a handful of visitors peer through the exhibits on a Tuesday morning.

Album covers showing the influence of ancient Egypt on artists such as Tina Turner, Earth Wind and Fire and Miles Davis have been installed near ancient objects.

One visitor said the Egyptian reaction to the “informative” exhibit made “no sense”. “Maybe they’re trying to score political points… Nothing to me was shocking,” said Daniel Voshart, 37, Canadian artist.

“It’s not like the Dutch government paid Beyoncé to become… Egyptian,” he told AFP.

Contacted by AFP, the museum declined to comment, but devoted a section on its website to the “agitation” around the exhibit.

The institution promised to erase offensive comments on its social media, and stressed that the exhibition aims to “show and understand the representation of ancient Egypt and musical messages by black artists” and “show what scientific and Egyptological research can tell us about ancient Egypt and Nubia”.

The curator of the exhibition, Daniel Soliman, is himself half-Egyptian and a big fan of music, sources at the museum said.

The exhibit, which opened in late April and will run through September, appears to have been embroiled in another controversy.

Pundits and Egyptian officials rose up in April after Netflix aired a production in which a black actress played the famous Queen Cleopatra, insisting she had “white skin”.

The Egyptian authorities a few months later banned the archaeologists from the Dutch museum of the Saqqara necropolis, south of Cairo, according to the Amsterdam newspaper NRC.

The museum staff had been active for almost five decades on the vast site known in particular for its pyramids.

Contacted several times by AFP, the authorities responsible for antiquities did not react.

But the controversy shows the difficulties when a country like the Netherlands – which has made efforts in recent years to come to terms with its colonial past – tries to embrace new perspectives, only to then run into a new set of problems.

“Egyptians have a very strong sense not only of Arab identity, but also of Egyptian Arab identity” while their relationship with Africa is more “complicated,” Ali Hamdan said.

But for this specialist in political geography from the University of Amsterdam (UvA), “it is not only a question of whether the museum understands Egyptian identity well or badly”.

“These are two different projects to make sense of ancient Egypt. One is a cultural project of this museum, and the other is a political project of the Egyptian state, which has a strong interest in deciding who belongs to ‘Egyptianness’,” he told AFP.