69 years old Age when hired: 17 years old Date started: April 26, 1971 Current position: trainer for about twenty years Family: 2 children and 6 grandchildren Place of residence: Saint-Odilon-de-Cranbourne

68 years old Age when hired: 17 years old Date started: March 22, 1972 Current position: receiving animals for about 40 years Family: 4 children and 10 grand children Place of residence: Saint-Joseph-de-Beauce

Location: Vallée-Jonction, in Chaudière-Appalaches Inauguration: 1965 Activities: slaughter and cutting of beef, veal and pork (initially). Today: pork only. Successive owners: Turcotte

Alain Nolet has worked in the same slaughterhouse for so long that when he was hired, he was earning $1,375 an hour. This rate to three decimal places was that of single men. Those who were married earned $1.50. His colleague Réjean Gagné entered it a year later, in 1972. The two Beaucerons were then 17-year-old teenagers who lived with their parents. Today grandparents, they still love their job and do not dream of retirement.

“When I’m off on a Sunday, I get bored,” says Réjean Gagné, who explains this feeling by routine, habit. He may be 68 years old, with over 51 years of seniority and “stuffed with arthritis”, but he still works every Sunday. With a good heart.

After five decades of box lunches, he’s not looking forward to having dinner at home every lunchtime.

In recent years, however, he has had the “luxury” of working only three days a week, since he is entitled to the Quebec Pension Plan, he explains to me. His colleague Alain Nolet, who has 52 years of seniority, also fell to three days in his mid-sixties. But he spends his summers mowing lawns and hedges for about fifty clients.

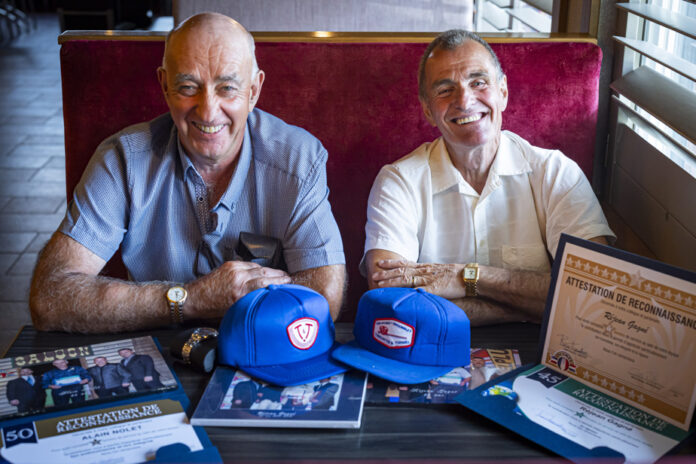

Seated in a restaurant with watches and commemorative plaques received over the decades, the two men tell me in detail about their first day in the Vallée-Jonction slaughterhouse. The same one that made headlines in 2021 during the strike, and again last spring when its permanent closure was announced by Olymel.

Alain Nolet worked in a bakery, where he earned 90 cents an hour. His boss had suggested that he find another job because he would soon no longer need his services. He applied for the slaughterhouse. One day, around 11:30 a.m., his mother came to the bakery to tell him that he had been hired. “You start at 1 o’clock!” Yes, the same afternoon!

The young man from Saint-Odilon spent his first hours “pushing fretted bacon attached to a rail”. He wasn’t sure he liked it, but 52 years later he can claim to have held just about every position. The multitude of steps between the reception of the animals and the packaging of the pieces of meat ready for sale no longer hold any secrets for him.

Approaching his 70th birthday, Alain Nolet is now a trainer. This role with young up-and-coming artists and temporary foreign workers, most of whom come from Africa, makes him feel “useful”, which he finds “very pleasant”.

Beside him, Réjean Gagné shows me a blue cap with the Turcotte logo.

Before working in meat, the teenager made cheese.

As soon as he had the chance, Réjean Gagné preferred to enter the slaughterhouse, which was only possible for those who had an internal contact. The working conditions were good, the weeks shorter, the frequent overtime paid accordingly.

He will never forget his first day. The boss had asked him to fill a truck with heavy animal skins (beef, veal) which were stored between layers of salt. A grueling, painful task. “Had to shake them up. I swear it didn’t smell too good. For a first day, it was a good test to pass! »

Today, he manages the animals that arrive by truck. A position he has held for forty years.

At that time, as soon as a young person left school, he had to work, relate the two men. Alain Nolet and Réjean Gagné lived in an agricultural environment, surrounded by farmers who worked 365 days a year. For them, that was a normal life.

The teenagers lived with their parents. So they used their pay to have fun, take a little break and spoil themselves between two shifts. Réjean Gagné quickly bought himself a brand new car “for $2400 or $2500”. It was a red 1972 Dodge Demon. “I didn’t have my license yet. In the evening when I came back from work, I sat in it and I did tricks in the yard. »

The work in the slaughterhouse, which requires endurance but also strong nerves, has never repelled or frightened them.

Alain Nolet knew what to expect, since at 12 or 13 years old, he was helping his grandfather who owned a small slaughterhouse. And he “loved” certain positions where there was a lot of noise. “Me, working in noise, I was freaking out over it. He even took on tough jobs that no one wanted to do because there was a 25-cent-an-hour bonus.

They were young, hardworking, ready to do anything and they wanted to make a name for themselves by accepting all the tasks that were asked of them, summarizes Réjean Gagné. They accumulated scars on their hands, forced themselves, exhausted themselves, but always in a good mood, playing tricks on each other. They did not dream of retirement in the sun or of trips to Europe.

They liked their job so much that five of the six children they had, in total, also worked at the slaughterhouse. Some during their studies, others full time. Sure, there were labor disputes, about “one to two conventions,” but they don’t have very painful memories of them.

To hear them talk, the idea of working elsewhere was never an option. “When you always work in the same place, you forget that there is work elsewhere…”, says Alain Nolet, a bit of a philosopher.

Stop to do what, exactly? they ask me in response. Alain Nolet saw his father work until he was 80. Retirement doesn’t seem to be a word in his vocabulary. He can’t imagine staying at home. Same thing for Réjean Gagné, who doesn’t really see the point of looking at the walls of his house. “Me, if it hadn’t closed, I would have worked another three, four, five years,” he blurts out. The closure announced by Olymel will force them to review their plans.

The slaughtering and cutting plant announced the end of its activities on December 22, 2023. Réjean Gagné is disappointed, bitter, sad. Obviously, he is grieving. “They were telling us we were the flagship. But the ship is sinking…” What will he do? He plans to “work for the government” during the 36 weeks of unemployment to which he will be entitled “even if we are going to be hassled to work elsewhere”. He has no specific plan.

His colleague Alain Nolet has already thought about his business: “I’m going to work at Maxi! I got myself a resume,” he says enthusiastically. Former colleagues from the slaughterhouse have been hired there. He also sees himself placing the food on the shelves. “Seems like I would like that!” »

Olymel workers have the right to be reimbursed $5,000 of purchases. How did they take advantage of it? “I put plaster on my house, I bought alpine skis, I’ve been doing them for 50 years, and I changed the floor in my kitchen,” replies Alain Nolet. For his part, Réjean Gagné has purchased a wood splitter and living room furniture.

“I had been working for about a month. They wanted me to go get a bull that had come in with a pocket on its head, it was so smart. I said no. A colleague said to me: “Shut up, little scary criss, I’m going to go,” says Réjean Gagné. He was less than three feet in the pen that the bull played with, braced him against the ceiling and released him. We went back to three guys to look for the guy who had almost been killed. It was broken all over. He didn’t work for three or four months. It marked me quite a bit. »

“One day, a pig ran away,” recalls Réjean Gagné, with a smile on his face. We found him on the edge of the river. He jumped in, he had his nose out, he was swimming. We didn’t know it was swimming, a pig! We took the company pick-up to pick him up. We come to catch the pig, but he jumps back into the water and crosses the river again. Arriving at the other side, the pig again crossed over to the other side. The vet told my colleague Gaston to get a rifle from him. Poor pig, he was exhausted. »