Aquariums, his previous book published in 2019, was described as anticipatory fiction, because it represented humanity grappling with an epidemic of unprecedented virulence. This therefore shows the extent to which we must be wary of the literary prophecies of J. D. Kurtness, who, in this third novel, imagines in the proverbially near future a Quebec company marketing small robots that look like children. Following a popular protest movement which saw these toys banned, one of these artificial kids, named Sim, had to take refuge in the countryside, with a farmer. “A modern-day Pinocchio,” they say.

At 82 years old, and with a dark sense of humor clearly intact, Yves Beauchemin warns that A Night of Storm will most likely constitute the end point of his generous work begun 50 years ago, because “writing senile, c It’s pathetic. Writing dead, extremely difficult.” Difficult to contradict him. The author of Le Matou and Juliette Pomerleau, master of the popular novel in its noblest expression, recounts in this potential last work the meeting between a man who had a nasty fall on an icy sidewalk and a dazed emergency doctor, who believes he recognizes in this patient his brother long gone.

In December 2021, Quebec literature lost one of its most endearing women. Both in the city and between the pages of his books, Abla Farhoud will have embodied empathy, humor and curiosity towards his neighbor. Her final work returns to the form of the choral novel, which she masterfully embraced in 2005 in Le fou d’Omar and in 2017 in Au grand soleil cachez vosfilles. Havre-Saint-Pierre thus encounters the voices of two aging brothers, who go on a pilgrimage in the footsteps of their sister, who died five decades previously. The writer’s daughter and eternal first reader, Alecka, supervised the editing work.

After the naturalization of John James Aubudon, to whom he gave flesh in The Twilights of the Yellowstone (2021), Louis Hamelin goes back again to the 19th century, the time of a novel dedicated to Henry David Thoreau. Allergic to idealized versions of history with a capital H, the author of La rage highlights the contradictions of one of the American thinkers still having the most influence on the contemporary life of ideas. His story Walden or life in the woods, chronicle of the two years, two months and two days that he lived in a cabin in the woods, obviously remains a bible for the environmental movement, as well as for the proponents of voluntary simplicity.

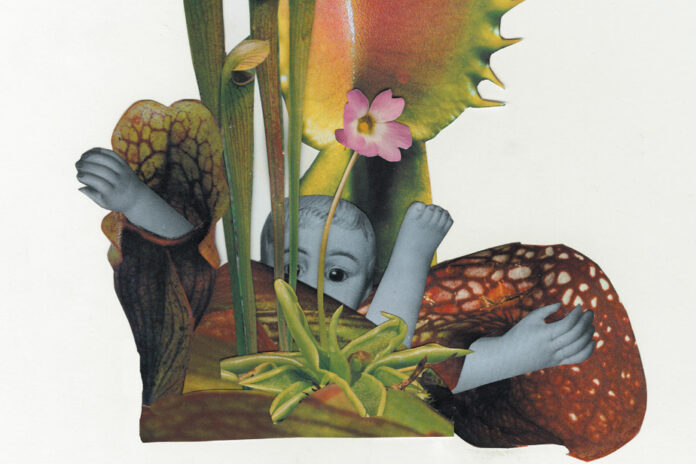

It goes without saying that children should be able to grow up free from all violence, but the world being what it is, kids are torn away from the blanket of their innocence every day by tragedy, war and injustice. It is partly around this idea that Larry Tremblay constructed his unforgettable novel L’orangeraie in 2016. A breeding ground from which he draws again between the pages of this collection of five short stories (or to use the chic term used by his publishing house, five “paintings”), guided by a dizzying question: “Why does Does childhood and hell share the same season? »

Nearly ten years after Métis Beach, her first novel acclaimed by critics and the public, Claudine Bourbonnais strips herself of the screen of fiction and embraces her own self in this story constructed from three personal memories. Between London, where she studied political science, Egypt, where she stayed for a summer to learn Arabic, and Montreal, where she discovered the true identity of a former classmate arrested during their transitioning to university, the anchor of Téléjournal weekend explores the fertile intersection between truth and memory. Intriguing.

In Tiohtiá:ke (2022), Michel Jean walked the distress-studded sidewalks of Montreal. He is now flying to Nunavik with Qimmik. The Innu writer recounts both the love between Saullu and Ulaajuk, who travel miles of ice and snow in the company of their dogs, and a few decades later, the thirst for justice of a non-indigenous lawyer called to defend an Inuk accused of murdering former police officers. But as is the case with several of his novels, including Kukum, it is implicitly the story of a vast territory – a place of freedom and dispossession – that the journalist tells the story here.

Four long years, that’s all the time – anxiety-inducing, nagging, interminable – that will last the legal process in which Léa Clermont-Dion engaged in October 2017, by filing a complaint against her former boss for sexual assault. Filing a complaint is also the title of the book that the documentary filmmaker (I salute you slut, Janette and girls) drew from this experience which was beginning while the movement

We knew he was gifted at making characters appear using a handful of finely chosen words and a few guitar chords. But it’s another kind of storyteller that Vincent Vallières revealed during his last solo tour, by publishing short road stories on social networks, all crossed by the conviction that as the title of his most recent album hopes , All beauty is not lost. These snapshots written at the level of a man and a woman, so many antidotes to the ambient mess, are finally put together under the same cover which, it is specified, will also contain many previously unpublished pieces.

Indigenous literatures have been shining for several years now, not only for their excitement, but also for the diversity of the texts they bring to the world. After a detour into the world of music with her incandescent minialbum Nui Pimuten, the essential Natasha Kanapé Fontaine returns to writing in this first collection of short stories subtitled “The Huntress”. The Innu novelist and poet announces a book pulsing to the rhythm of a “merciless territory”, a work made “of surrealism, magical realism, dreamlike, fantastic or real creatures from oral tradition and spirits of the ‘ancestral animism’.