Almost every week, Brian Levine, a computer scientist at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, gets asked this question by his 14-year-old daughter: Can I download this app?

Mr. Levine then sifts through hundreds of customer reviews in the App Store with keywords like “harassment”, “sexual abuse” and “child”. This manual and arbitrary process gave him the idea for a tool to help parents quickly evaluate apps.

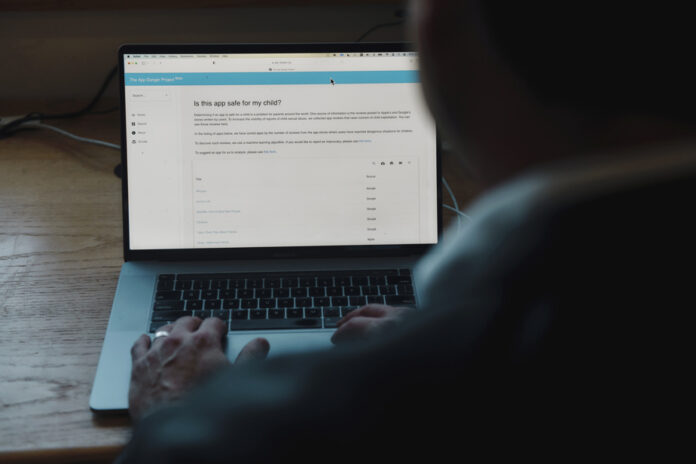

For the past two years, Levine has been working on a computer model that evaluates customer feedback on apps. Using artificial intelligence (AI) to assess the context of comments containing words like “child porn” or “pedo,” Levine and a team of researchers created a searchable website called the App Danger Project, which provides clear advice on the security of social networking applications.

The website tracks reports of sexual predation and assesses the safety of apps that have received negative feedback. It lists reviews mentioning sexual abuse. The team did not follow up on the veracity of the comments, but read them all and excluded those that did not report a safety issue for children.

Predators are increasingly using apps and the internet to collect explicit images. Last year, US police received 7,000 reports of young people being tricked into sending naked pictures and then being blackmailed into getting more photos or money. The FBI does not reveal how many of these reports were credible. These events, called sextortion, have more than doubled during the pandemic.

Because the App Store and Google Play don’t offer keyword search, it can be difficult for parents to find warnings of inappropriate sexual behavior, Levine says. He says the free App Danger project complements other services that assess whether products are suitable for children — such as Common Sense Media — by identifying apps that aren’t monitoring users enough. Its site is not for profit, but encourages donations to the University of Massachusetts to offset its costs.

Mr. Levine and a dozen computer scientists studied the number of notices of child sexual abuse in more than 550 applications distributed by Apple and Google.

Their investigation builds on previous reports of apps with complaints of unwanted sexual interactions. In 2019, The New York Times explained how predators use video games and social media platforms as a hunting ground. That year, a separate Washington Post report found thousands of complaints about six apps, leading Apple to remove the Monkey, ChatLive, and Chat for Strangers apps.

Apple and Google have a financial interest in distributing apps. The tech giants, which claim up to 30% of app sales, helped three apps that many users reported sexual abuse generate $30 million in sales last year: Hoop, MeetMe and Whisper, according to Sensor Tower, a market research firm.

In more than a dozen criminal cases, the Justice Department has described these apps as tools used to ask children about sexual images or encounters: Hoop in Minnesota, MeetMe in California, Kentucky, and in Iowa, and Whisper in Illinois, Texas and Ohio.

Mr. Levine said that Apple and Google should provide parents with more information about the risks of certain applications and better monitor those that have already been the subject of reports.

Apple and Google say they regularly analyze app reviews using their own computer models and that they investigate claims of pedopredation. Applications that violate their policies are removed. Apps are categorized by age to help parents and children, and software allows parents to block downloads. The two companies also offer application developers tools to control sexual content intended for children.

A Google spokesperson said the company reviewed apps listed by the App Danger Project and found no evidence of child pornography.

“While user comments play an important role as a signal to trigger further investigation, allegations drawn from comments are not sufficiently reliable on their own,” he said.

Apple also reviewed apps listed by the App Danger Project and removed 10 that violated its distribution policies. The company declined to provide a list of these apps and its reasons for doing so.

“Our App Review team works 24/7 to carefully review each new app and app update to ensure they meet Apple’s standards,” a carrier said. speech in a press release.

The App Danger project said it found a significant number of comments suggesting that Hoop, a social networking app, was not safe for children; for example, it found that 176 of 32,000 comments since 2019 reported pedopredation.

Hoop, which is under new management, has a new content moderation system to enhance user safety, said its CEO, Liath Ariche, adding that researchers have shed light on the difficulties had the founders to counter malicious users. “The situation has improved a lot,” says Mr. Ariche.

The Meet Group, which owns MeetMe, said it does not condone the abuse or exploitation of minors and uses artificial intelligence tools to detect predators and report them to law enforcement. He reports any inappropriate or suspicious activity to authorities, including a 2019 episode in which a Raleigh, North Carolina man solicited child pornography.

Whisper did not respond to requests for comment.

Apple and Google submit hundreds of reports to the US Child Sexual Abuse Clearinghouse each year, but don’t say whether some of those reports are app-related.

Whisper is one of the apps that Levine’s team has found are often criticized for sexual exploitation. After downloading the app, a high school student in 2018 received a message from a stranger offering to help fundraise for a robotics school in exchange for a topless photo. After she sent a photo, the stranger threatened to send it to her family if she didn’t provide more images.

The teen’s family reported the incident to local law enforcement, according to a report from the Mascoutah, Illinois, police department, which later arrested local man Joshua Breckel. He was sentenced to 35 years in prison for extortion and child pornography. Although Whisper was not held responsible, it was named, along with half a dozen apps, as the main tool he used to collect images of victims between the ages of 10 and 15.