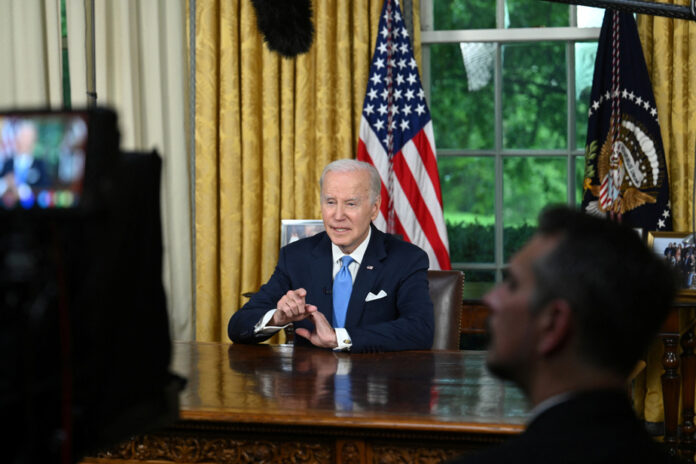

The United States narrowly avoided a default when President Joe Biden signed legislation on Saturday allowing the cash-strapped Treasury Department to borrow more money to pay the country’s bills.

Today, the Treasury is starting to rebuild its reserves and the next wave of borrowing could lead to complications that will shake the economy.

According to estimates by several banks, the government should borrow about $1 trillion by the end of September. This steady borrowing trend is expected to draw cash from banks and other lenders into Treasury securities, draining money from the financial system and amplifying pressure on already struggling regional lenders.

To induce investors to lend such large sums to the government, the Treasury must deal with rising interest costs. Since many other financial assets are tied to the treasury bill rate, higher borrowing costs for the government also lead to higher costs for banks, businesses and other borrowers, and could have an impact similar to that of one or two quarter-point rate hikes from the Federal Reserve, analysts warned.

“The root cause remains the impasse over the debt ceiling,” said Gennadiy Goldberg, interest rate strategist at TD Securities.

Some policymakers have indicated they may choose to pause rate hikes at the central bank meeting next week to assess the impact of policy so far on the economy. . The replenishment of Treasury liquidity could jeopardize this decision, as it would lead to higher borrowing costs.

This, in turn, could exacerbate investor and depositor concerns that surfaced in the spring about the erosion in the value of assets held by small and medium-sized banks due to rising interest rates.

The deluge of Treasury debt also amplifies the effects of another Fed priority: shrinking its balance sheet. The Fed has reduced the number of new Treasuries and other debt securities it buys, slowly letting old securities trickle down and already leaving private investors with more debt to digest.

“The potential impact on the economy when the Treasury sells off such an amount of debt could be extraordinary,” said Christopher Campbell, who served as assistant secretary to the Treasury for financial institutions from 2017 to 2018.

The Treasury’s general account balance fell below the $40 billion mark last week as lawmakers struggled to reach an agreement on raising the nation’s borrowing limit. Legislation signed by Mr. Biden on Saturday suspends the $31.4 trillion debt limit until January 2025.

For months, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen resorted to accounting maneuvers known as “extraordinary measures” to delay a default. In particular, it suspended new investments in the pension funds of postal workers and civil servants.

Restoring these investments is essentially a simple accounting solution, but filling the state coffers is more complicated. The Treasury Department said Wednesday it hoped to borrow enough to replenish its cash account to $425 billion by the end of June. Analysts say he will have to borrow significantly more than that to account for planned spending.

“The supply floodgates are now open,” said Mark Cabana, interest rate strategist at Bank of America.

A Treasury Department spokesperson said that when making decisions about issuing debt, the department carefully considered investor demand and market capacity. In April, Treasury officials began polling major market players to find out how much they thought the market could absorb after the debt limit impasse was resolved. This month, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York asked major banks for their views on developments in bank reserves and borrowings from certain Fed facilities over the coming months.

The spokesperson added that the department has handled similar situations in the past. Notably, after a row over the debt ceiling in 2019, the Treasury Department rebuilt its cash flow over the summer, contributing to factors that drained reserves from the banking system and upset market mechanics, which prompted the Fed to intervene to avert a deeper crisis.

In particular, the Fed has set up a program to buy back agreements, a form of financing with Treasury debt as collateral. This backstop could allow cash-strapped banks to lend to the government, although its use was widely seen in the industry as a last resort.

A similar but opposite program, which hands out Treasury guarantees in exchange for cash, currently holds more than $2 trillion, mostly from money market funds that have struggled to find attractive and safe investments. Some analysts consider it to be pending money that could be poured into the Treasury account when it offers better interest rates on its debt, reducing the impact of the frenzy. loans.

But the mechanism by which the government sells its debt, debiting bank reserves held at the Fed in exchange for new bills and bonds, could still test the resilience of some smaller institutions. As their reserves dwindle, some banks may find themselves short of cash, while investors and others may be unwilling to lend to institutions they view as struggling, given recent concerns over certain sectors of industry.

Some banks could then depend on another Fed mechanism, put in place at the height of this year’s banking turmoil, to provide emergency funding to depository institutions at relatively high cost.

“One, two or three banks may be caught off guard and suffer the consequences, which would set off a chain of fear that would ripple throughout the system and create problems,” said TD’s Goldberg. Securities.

This article originally appeared in the New York Times.