Presented less than a decade ago as replacements for printed books, electronic readers are experiencing a slow decline. And if the Quebec reader could count on around ten manufacturers, there are only two left today, Kobo and Amazon, to compete for their favors. Are e-readers about to join Betamax, plasma televisions and the BlackBerry in the graveyard of good ideas? Or have they simply found their modest niche?

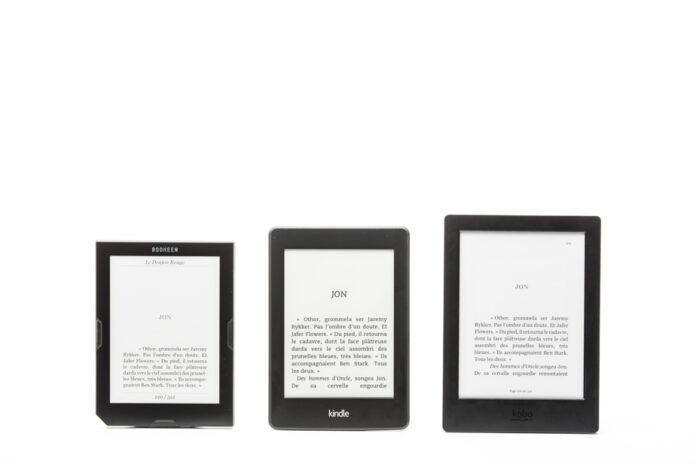

The e-reader is not doing very well, and companies like Sony and Icarus have understood this by leaving this market, while others like Bookeen and Nook are barely offered outside their territory. Even Kobo and Amazon, the two undisputed leaders, have slowed down and are releasing few new models.

Analysts prove them right: this market is clearly in decline, as indicated by this table compiled by Statista, whose data unfortunately ends in 2016.

The firm 360 Research has more bad news. It estimates revenues from this industry at US$383 million in 2020, and forecasts revenues to be US$100.5 million in 2027.

This small device, generally weighing less than 300 grams with a screen under 8 inches, is specifically designed for reading. It differs from a tablet by the low power of its processor, which makes it unsuitable for web browsing or using applications. Its “electronic ink” screen does not need constant refreshing and gives the e-reader a battery life that is calculated in weeks, rather than days for a tablet. Backlighting, blue light filtering orange tint, touch screen and storage capacities up to 64 GB are now common in the models offered. Some manufacturers have launched larger, more powerful and more expensive models in recent years.

Unlike e-readers, books in electronic format are undeniably popular. The global market has been estimated, depending on sources, to be worth US$12-16 billion in 2022 and is expected to grow at a modest but steady annual rate of around 2% over the next five years.

Quebec public libraries are seeing this enthusiasm, lending “between 8,000 and 10,000 digital books” every day, specifies Jean-François Cusson, director of service development and mediation at Bibliothèque et Archives nationaux du Québec (BAnQ). In 2012, he helped set up the digital book lending platform for libraries with the Bibliopresto organization.

“Digital loans have become almost as strong as paper loans,” he believes. It’s huge, but it’s something that is by definition invisible. »

Mr. Cusson does not have precise statistics on the percentage of readers using an e-reader, but he is not convinced that the device is on its way out. “On public transport, I see people every day with e-readers […] It’s true that many manufacturers have disappeared in Quebec, but in Europe, there is more competition, with PocketBook and Vivlio. »

At Best Buy Canada, we also sound more optimistic about this category of products, of which we offer no less than 15 models in store. “It’s surprising,” admits Thierry Lopez, marketing and corporate affairs director in Quebec at Best Buy Canada. There was a craze during the pandemic, and the craze has continued since. » If we offer 15 models, he notes with a laugh, “it’s because [there] are customers for that.”

Ruth Guay, from Trois-Rivières, is one of these clients. She is one of those e-reader lovers who has found the ideal medium. “It’s so light. And I often read in the evening while I go to bed, so having this orange light adds a lot to the comfort. I never thought I would read a book on an iPad. »

However, she agrees that she is an exception in those around her. “My friends tend to favor paper. The attachment to the paper book, I can understand. But when traveling, the facilitating aspect of the e-reader wins out. »

Chloé Baril, who took over from Mr. Cusson as general manager of Bibliopresto.ca last July, believes that the e-reader has simply found its niche. A much more modest place than what was expected from 2007 when Amazon Kindles appeared, “but not all the space as we announced”.

The reason, she analyzes: tablet manufacturers were able to adjust to the advantages that e-readers seemed to provide. “I was at BAnQ at the time, I heard people saying that their iPad was too bright, heavier than an e-reader. The manufacturers have noted these criticisms and have added sepia lighting, accessibility tools that allow the character to be enlarged, the contrasts to be adjusted, and voice synthesis to be available. »

Ms. Baril had recent confirmation of this, with a survey conducted last April by the Quebec firm De Marque, an important partner of Bibliopresto: users of public libraries prefer to read their digital books on a tablet or a phone.

Among frequent borrowers, for example, those who borrow e-books more than once a month, 64% read them on the mobile app for tablets and phones. The e-reader: 23%.

“The mobile app comes first, but the e-reader is not insignificant. »

She agrees, however, that this market appears to have lost momentum. “There has clearly been a ‘semi-abandonment’ of several manufacturers, this is a commercial decision. It’s a bit like the disappearance of iPods. Why did they disappear? We don’t know, it worked well, I still have a Shuffle and I use it while doing my dishes because it’s practical. »

Ms. Baril believes that the industry has not helped its cause by trying to impose increasingly closed ecosystems. Amazon Kindles cannot read books borrowed from the library and Quebec Kobo users must multiply the manipulations to achieve this.

“The e-reader market has sabotaged itself a bit [“jinxé”], summarizes the general director. When Amazon decides that its e-reader only reads Amazon, that we create a captive market, it’s a no-brainer. It could lead to what happened with the iPhone or make people turn to something else. »