For more than a century, promoters of motor sports have been insisting that competition renders proud services to the automobile of Mr. Mrs. Everyone. Don’t believe it. Rather, the reverse is true.

On the other hand, the race – and therein lies its usefulness – allows all parties involved (manufacturers, craftsmen, equipment manufacturers, suppliers) to demonstrate their mastery of the technology. Which allows you to sell better, hence the American expression “Win on Sunday, sell on Monday”.

Power steering, hybrid engines and even 18-inch tires existed long before they entered Formula 1. synthetic.

Again, she is not the first to cross the finish line. The origin of this process goes back more than a century and is attributed to two German chemists, Franz Fischer and Hans Tropsch.

Other disciplines of motorsport (Endurance, Rally, Indy) have also been feeding for some time on a (more) green fuel generally composed of ethanol and non-food biomass. According to Shell, IndyCar’s incumbent, one of the challenges is to make this 100% renewable fuel compatible with the current structure of the internal combustion engine.

Same story with Total, official supplier of the World Endurance Championship (WEC). The French oil company provides competitors with a 100% renewable fuel which leads to a 65% reduction in CO2 emissions.

In addition, several environmental organizations question the effectiveness of this essence. This not only consumes a lot of energy, but is also incredibly complex to produce. The capture of CO2 in the atmosphere is a good example. All arduous steps that are “rewarded” by a performance judged, so far, very disappointing by specialists in the field.

Formula 1 wants to go further and claims that its research will lead to a technological breakthrough. And this, thinks Pat Symonds, Formula 1’s technical director, will not only benefit all combustion engine vehicles (F1 estimates that despite electrification, more than 1.8 billion gasoline-powered vehicles will still be in circulation in 2030), but also to the transport industry (air, sea and land). The question remains: at what cost?

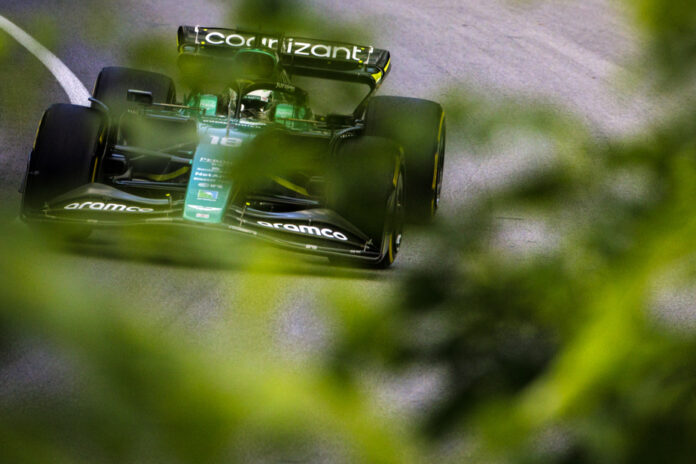

Until this new fuel enters the scene, Formula 1 can still ride on its progress of recent years. Even if the Formula 1 cars that will storm the Gilles-Villeneuve circuit this weekend will consume an average of 45 L/100 km. It’s a lot, but not much. When Jacques Villeneuve was driving, Formula 1 cars swallowed almost double that.