Rio Tinto does not consider places other than Quebec to produce the 100% green aluminum promised by its revolutionary Saguenay technology, Elysis. However, the company sets one essential condition: preferential tariffs, even if energy is increasingly scarce.

At the head of the aluminum division of the multinational, Ivan Vella concedes that Quebec aluminum smelters are the most profitable in the world. The picture is different when it comes time to build new facilities, hence the need to obtain energy rebates, says the businessman.

In an interview with La Presse for about 90 minutes, the businessman defended tooth and nail the demands of the Australian-British mining giant despite all the privileges he already enjoys. Last December, La Presse revealed that Rio Tinto had paid virtually no taxes to the Quebec government in recent years for its aluminum sector. The company also has the right to produce its own electricity on the Saguenay and Péribonka rivers, at low cost.

Mr. Vella echoed a refrain that has been heard more than once in the past when he spoke of keeping well-paying jobs outside major urban centers – even in the face of labor shortages – and significant economic benefits for many suppliers. Added to this are annual investments of around half a billion made by Rio Tinto in the maintenance of its Quebec facilities, he adds.

The boss of Rio Tinto Aluminum wanted to dispel doubts after causing concern. Last fall, he said that the Elysis technology could not be implemented in Quebec aluminum smelters because they are too old.

It is indeed “very difficult” to upgrade an existing aluminum smelter, Vella acknowledged in an interview. He “crosses his fingers” that this scenario can happen, without however having any illusions. The deployment of this new technology may require the construction of new facilities.

“That’s the most plausible strategy,” says Vella.

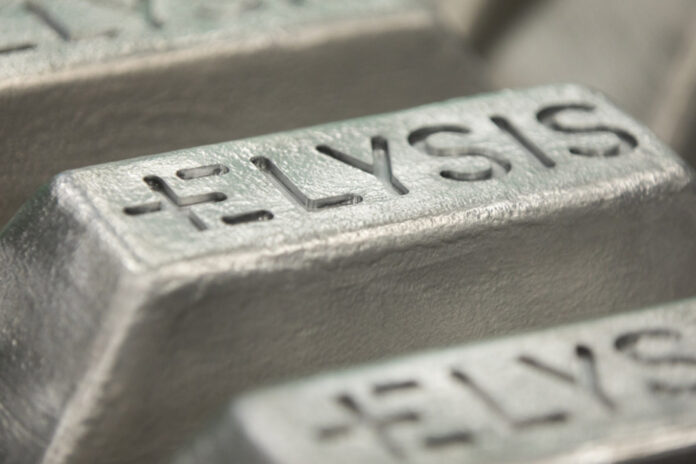

In development in Saguenay since 2018, Elysis is considered very promising, but it is still in its infancy. Rio Tinto, Alcoa and Apple are financing part of the project. However, it is the governments of Ottawa and Quebec that have mostly loosened the purse strings so far by offering 120 of the 228 million needed.

The first steps of the commercial phase of this new technology should take place at the Alma site, explained Mr. Vella. The reason is simple: there is space to accommodate new tanks.

“There is a half-line of space [for tanks] ready to be expanded,” says the Rio Tinto executive. It’s no surprise that the first three vats are part of this line which is expected to continue with Elysis. The first large-scale [phase] can be done on a virgin site, but integrated with Alma. Then we will have to think about what we will do for the rest. »

According to Mr. Vella, there is talk of a project with an annual capacity of 170,000 to 200,000 tonnes of silver metal at the Alma complex. If all goes as planned, the commercialization of this new technology is scheduled for 2030. Rio Tinto is counting on the willingness of its customers to pay more for aluminum produced without greenhouse gas emissions.

The Minister of Economy, Innovation and Energy, Pierre Fitzgibbon, repeats that the Elysis technology will make Quebec a leader in the production of green aluminum in the world. He is open to the possibility of granting more electricity at preferential rates to Rio Tinto. It is unclear, however, what the price will be paid by the company.

The head of Rio Tinto’s Aluminum division was cautious in commenting on the state of negotiations between the multinational and the Legault government. For decades, aluminum smelters were able to benefit from preferential hydroelectric rates while surpluses were the norm at Hydro-Québec.

Aware that the context has changed and that the Quebec government’s bargaining power is much greater. Mr. Vella issues a warning, however.

“Quebec can say ‘here’s what the price will be’ and we’ll say ‘OK, we just can’t invest at that price,'” he warns. They know that. We recognize that we need to partner with the province to ensure that the balance is right. »

“What they [the government] don’t want to see are Quebec aluminum smelters added to this list of closures because of the good jobs we are generating,” he said. There’s a balance to be struck and that’s the conversation we need to have [with the government]. »

In the wake of remarks made last November by Mr. Vella, former Rio Tinto executives challenged the Legault government, La Presse reported last month. They asked Quebec not to believe everything that Rio Tinto promises. One of them, Jacques Dubuc, felt that the signals “coming from the company” did not bode “nothing good for the future of the existing facilities in the Saguenay”.

After taking its first steps in the Quebec sector of batteries for electric vehicles last year, Rio Tinto does not seem to want to slow down. Whether on the extraction or processing side, the multinational is considering other advances in this new market.

“There are probably about 50 people [in Quebec] working on the battery materials file,” said Rio Tinto Aluminum President and CEO Ivan Vella. We look at lithium, nickel, copper and scandium. »

In the niche of critical metals, the multinational has developed a technology to produce three tonnes of scandium annually, a critical mineral used by the aerospace and electronics industry – for which demand is rising sharply.

It also made a $10 million investment in Nano One, a Vancouver-based company that manufactures cathodes – a critical component of the lithium-ion battery found in electric vehicles. In the lithium sector, Rio Tinto is also completing the construction of a complex in Argentina to extract this gray metal.

Asked if this was a model that Rio Tinto could replicate, Vella said yes.

“Yes, of course,” he said. Develop or acquire [a project], absolutely. We want to transform as much as possible. This is the technology we are working on. »

Since the start of the pandemic, demand for semiconductors – components found in electronic chips essential to the operation of technological devices – has risen sharply. Rio Tinto is trying to take advantage of this by recovering some of the bauxite residue.

“Guess what is filled with gallium [needed in semiconductors]? Bauxite tailings, Vella points out. We are working very hard to filter and recycle these bauxite residues. »

At its Vaudreuil alumina refinery in Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean, the company has a bauxite residue filtration and optimization plant, which was commissioned in 2019.